Why four whale species defy typical mammalian reproduction

Survive and reproduce. Survive and reproduce. The refrain of natural selection that guides billions of species towards safety and sex should be easy to follow (1). Basic Darwinian logic dictates that individuals who remain fertile for as long as possible will beget more offspring and a greater influence on the gene pool (2). For four whale species, however, an alternative narrative of “less is more” appears to prevail instead. Like humans, killer whales, short-finned pilot whales, beluga whales, and narwhals all undergo menopause, losing their reproductive capacity decades before death (6).

Menopause among cetaceans should not be confused with human menopause – young orcas don’t spill blood into the ocean once per month (10). In fact, scientists discovered the phenomenon of whale menopause by measuring the average age at which female whales cease reproduction (3). Although a thirty-two-foot-long killer whale can live past the age of ninety, most female orcas stop giving birth in their mid-thirties (11). Currently, scientists do not know whether whales experience the physiological symptoms of humans in menopause (hot flashes, vaginal dryness, etc.), but the creatures could certainly undergo symptoms as well (10).

The most obvious question to ask about menopause – in humans or whales – is why it occurs at all. In almost all other mammalian species, matriarchs continue to give birth until a year or two before they die, indicating that Darwin’s theory of maximizing reproduction tends to work in practice (12). Even baleen whales reproduce into their nineties (references to “whales” in the rest of this article refer exclusively to the four species mentioned in the introduction) (8).

Three main hypotheses offer insight into why whales undergo this peculiar phenomenon. The first involves the risk to mother and child. Childbirth is a dangerous process, and each additional birth offers the potential for serious harm to befall the woman or whale giving birth. Especially in the wild, orphaned whales with no kin to support them face massive disadvantages, so the subsequent harm to a mother whale’s existing descendants may eventually offset the evolutionary advantage of having another child (2).

This first hypothesis, however, likely holds better among humans than it does whales, for whom giving birth has historically presented more of a risk (6). Although dangers associated with childbirth likely assisted the shift towards menopause for whales, they were probably not the biggest factor (2).

The second – and more widely accepted – hypothesis is that older female whales can ensure that their descendants survive by contributing to their grandchildren’s upbringing rather than having more children of their own. This theory is known as the “grandmother” hypothesis and is backed up by whale behavior in the wild (8). In 2012, a team of scientists led by researcher Ken Balcomb demonstrated that whales, especially male whales, depend on their mothers, to the extent that an adult male whale with a postmenopausal mother becomes fourteen times more likely to die in the next year if she passes (1). In fact, sons seem to depend on their mothers more as time goes on, rather than less – an older recently orphaned whale is more likely to die than a younger one.

A female whale’s assistance to her children and grandchildren likely stems from the knowledge that she has gained and her greater skill in finding food and safe passage (5). Since both whale sons and daughters stay with their families, a whale matriarch is responsible for her entire pod, more and more of whom she will be related to as her children reproduce (1). One orca, centenarian “Granny” or J2, led a pod of twenty other whales, all of whom she was related to (3). Researchers noted her ability to communicate with other pods by moving her tail. As humans have done for centuries, whales develop the equivalent of tribal elders, whose value comes not in child-rearing but imparting wisdom – encyclopedias of hunting squid, and navigating (2).

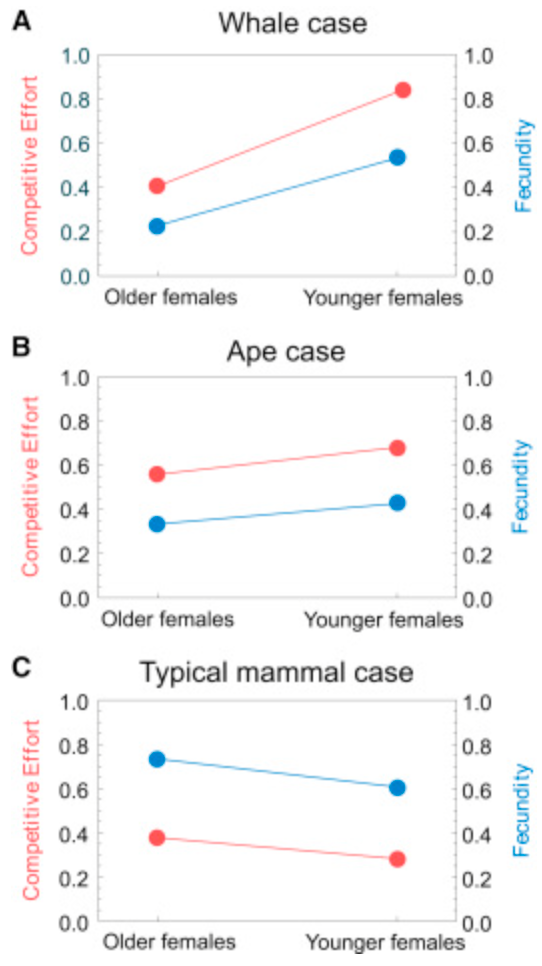

Still, elephant matriarchs, who are also large and impart knowledge to herds, accomplish all the same goals while giving birth, so scientists searched for a third hypothesis that would fill in the missing gaps of whale menopause. Originally proposed by Michael Cantand Rufus Johnstone in 2007, the “reproductive conflict hypothesis” offers a distinction between whales and similar animals (9). The theory predicts that the offspring of an elder generation of whale mothers will compete with the offspring of their daughters for limited resources, and that the children of older mothers will find it difficult to survive (8). Among whale pods, where resources are especially scarce, younger mothers will have little genetic investment in the rest of the pod, and prioritize their offspring more than distant relations (1). In contrast, older mothers are spread thin over their other children and can devote less individual attention to new ones. A 2017 study run by Darren Croft of Exeter University backed up this hypothesis using data, finding that young children of older whales have mortality rates that are 1.7 of their competitors (8).

This phenomenon is unique to whales, largely due to the demography of their family groups. Elephant sons and male offspring of most mammals leave the herd, meaning that older elephant females are not surrounded by their children, making it easier for them to compete for resources (1). Whale mothers, in contrast, will live with their daughters forever, meaning that cooperation, not competition, is their best strategy to maximize genetic influence (8).

Risk during childbirth, the grandmother effect, and reproductive conflict all play a role in the evolution of whale menopause, but from an anthropological standpoint, they also hint at the answer to the question of why human women stop reproducing in their early fifties. More research into menopause may also grant insight into the life cycles of other species. Belugas and narwhals, the fourth and fifth creatures to join the menopausal list, were only added in 2018 (12). Perhaps other creatures living below the surface of the ocean are more similar to humans than we think.

Bibliography

- Yong, E. (2017, January 12). Why Killer Whales (and Humans) Go Through Menopause. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/01/why-do-killer-whales-go-through-menopause/512783/

- Diamond, J. (1997). Why Is Sex Fun. Basic Books.

- McKie, R. (2017, January 15). Killer whales explain the mystery of the menopause. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/jan/15/killer-whales-explain-meaning-of-the-menopause

- Arnold, C. (2019, December 9). Why do orca grandmothers live so long? It’s for their grandkids. National Geographic. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/orcas-killer-whales-menopause-grandmothers.

- Gill, V. (2016, August 11). What can killer whales teach us about the menopause? BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-37025092

- Ellis, S. Franks, D. Nattrass, S., Currie, T., Cant, M., Giles, D., Balcomb, K., Croft, D. (2018, August 27). Analyses of ovarian activity reveal repeated evolution of post-reproductive lifespans in toothed whales. Nature. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-31047-8

- Caruso, C. (2017, May 1). A New Theory for Why Killer Whales Go Through Menopause. Scientific American. Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/a-new-theory-for-why-killer-whales-go-through-menopause/

- Croft, D. (2017, January 12). Reproductive Conflict and the Evolution of Menopause in Killer Whales. Current Biology. Retrieved from https://www.cell.com/current-biology/comments/S0960-9822(16)31462-2#back-bib6

- Cant, M., Johnstone, R., (2008, April 8). Reproductive conflict and the separation of reproductive generations in humans. National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Retrieved from https://www.pnas.org/content/105/14/5332

- Smith, R. (2013, October 21). Hot Flashes in Cold Waters? Killer Whales Undergo Menopause. National Geographic. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/131019-killer-whales-menopause-hot-flash-marine-mammals

- Killer Whale. NOAA Fisheries. Retrieved from https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/killer-whale.

- Seamons, K. (2018, August 29). 3 species were known to go through menopause – now it’s 5. Fox News. Retrieved from https://www.foxnews.com/science/3-species-were-known-to-go-through-menopause-now-its-5.

- Platt, J. (2016, June 4). Sperm Whales have an “Eve”. Hakai Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.hakaimagazine.com/news/sperm-whales-have-eve/.