Circadian rhythms control everything from sleep to digestion.

Have you ever wondered why you feel so sluggish in the morning, wide awake late at night, or disoriented after crossing multiple timezones? That’s thanks to your circadian rhythm—a physical, mental, and behavioral change experienced over a 24-hour cycle. In every cell of your body, a biological clock ticks and influences how you feel. This timekeeper is driven by proteins, following thousands of genes that alternate between on or off in a precise sequence. These alterations not only determine sleeping patterns but also shift your appetite and digestion, hormone release, and even body temperature (1). At night, you might prefer a cooler room, as your circadian rhythm lowers your body temperature. When you feel tired in the morning, it’s your circadian rhythm at work, signaling that your body should rest. The disorientation after crossing time zones is not random but a result of your internal clock shifting to adjust to a new schedule.

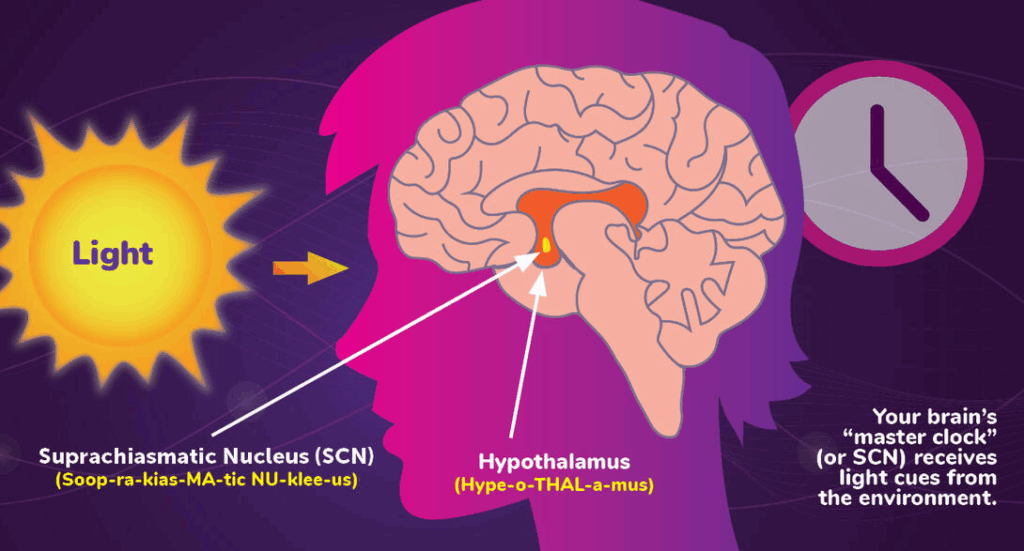

It’s not just humans that have this biological process. Most living things, including animals, plants, and microorganisms, have functional circadian rhythms that help them survive (1). For humans, the circadian rhythm connects to an internal clock in the brain. This internal timekeeper is found in a tiny bunch of cells known as the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), located in the brain’s hypothalamus where hormones are released (2). Internal clock genes in the SCN send signals to control the activity throughout the body during the day. The SCN directly uses light to coordinate the circadian rhythms in the body (2). Therefore, day and night are directly related to circadian rhythms; however, stress, physical activity, and social environments can also affect them. When someone scrolls on their phone late at night, the light on the screen prompts the SCN to send a message around the brain to halt melatonin production, a hormone that aids in sleep. This is why many people advise against watching screens before bed, and why you might have trouble sleeping after watching your phone.

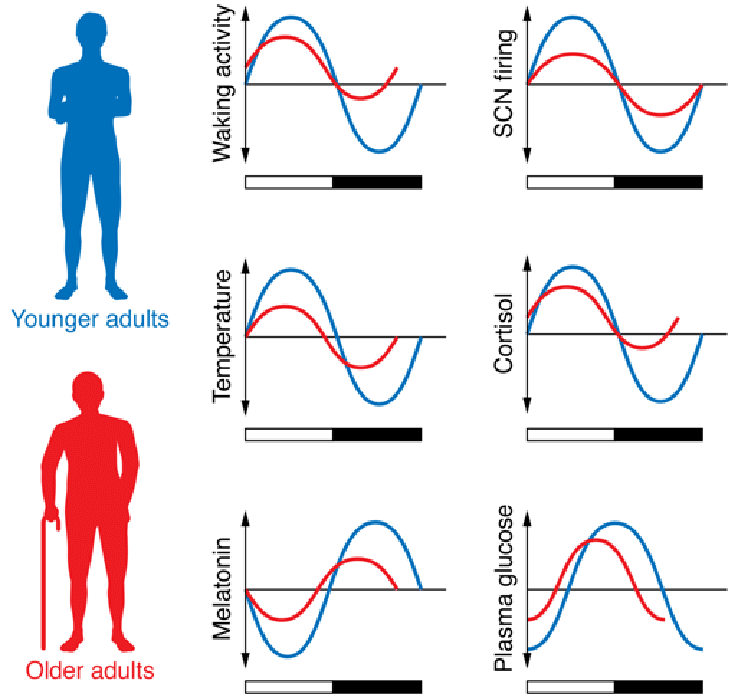

Besides the environmental factors of a healthy circadian rhythm, the circadian cycle is also determined through age and genetics. An individual human’s circadian period length can be significantly shorter or longer than the 24.2 hour average (3). In fact, the slight differences in circadian periods are known as chronotypes. These chronotypes determine why someone might feel more alert in the morning, while others prefer sleeping late at night. They also determine how many hours of sleep a person can function on (4). Early chronotypes, often referred to as “morning birds,” thrive during the first hours of the day, while late chronotypes find peak productivity in the evening; however, these preferences are not fixed and can shift dramatically with age and environmental factors (2). At birth, circadian rhythms are still developing, so newborns must adjust before forming stable sleep-wake patterns. Later, with puberty and increased use of electronics, circadian rhythms tend to shift later in time, explaining why teenagers tend to stay up late (1). On the contrary, in adulthood, circadian rhythms tend to drift back again, leading to more “morningness” with aging. This shift continues as circadian rhythms continue to drift earlier in time for the elderly (4).

Circadian rhythms are more than just internal clocks that let you know when it is day or night—they are precisely tuned systems that affect how we sleep, eat, and function. These rhythms adapt to external factors like light and evolve with age. From newborns to the elderly, the shifting patterns of circadian rhythms reveal how deeply connected we are to the world around us. So, the next time you feel tired in the morning or restless at night, remember, it’s your circadian rhythm at work, keeping your body in sync with its natural cycle.

Works Cited

- Circadian Rhythms | National Institute of General Medical Sciences. (2017). Nih.gov. https://www.nigms.nih.gov/education/fact-sheets/Pages/circadian-rhythms

- Clinic, C. (2024, March 18). Circadian Rhythm: What It Is, How It Works & What Affects It. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/circadian-rhythm

- Gentry, N. W., Ashbrook, L. H., Fu, Y.-H., & Ptáček, L. J. (2021). Human circadian variations. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 131(16). https://doi.org/10.1172/jci148282

- Burgess, H. J., & Swanson, L. M. (2020, April 30). Circadian Rhythms Across the Lifespan. Psychiatric Times. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/circadian-rhythms-across-lifespan

Comments are closed.