In Vitro Human Replicas on a Fingertip

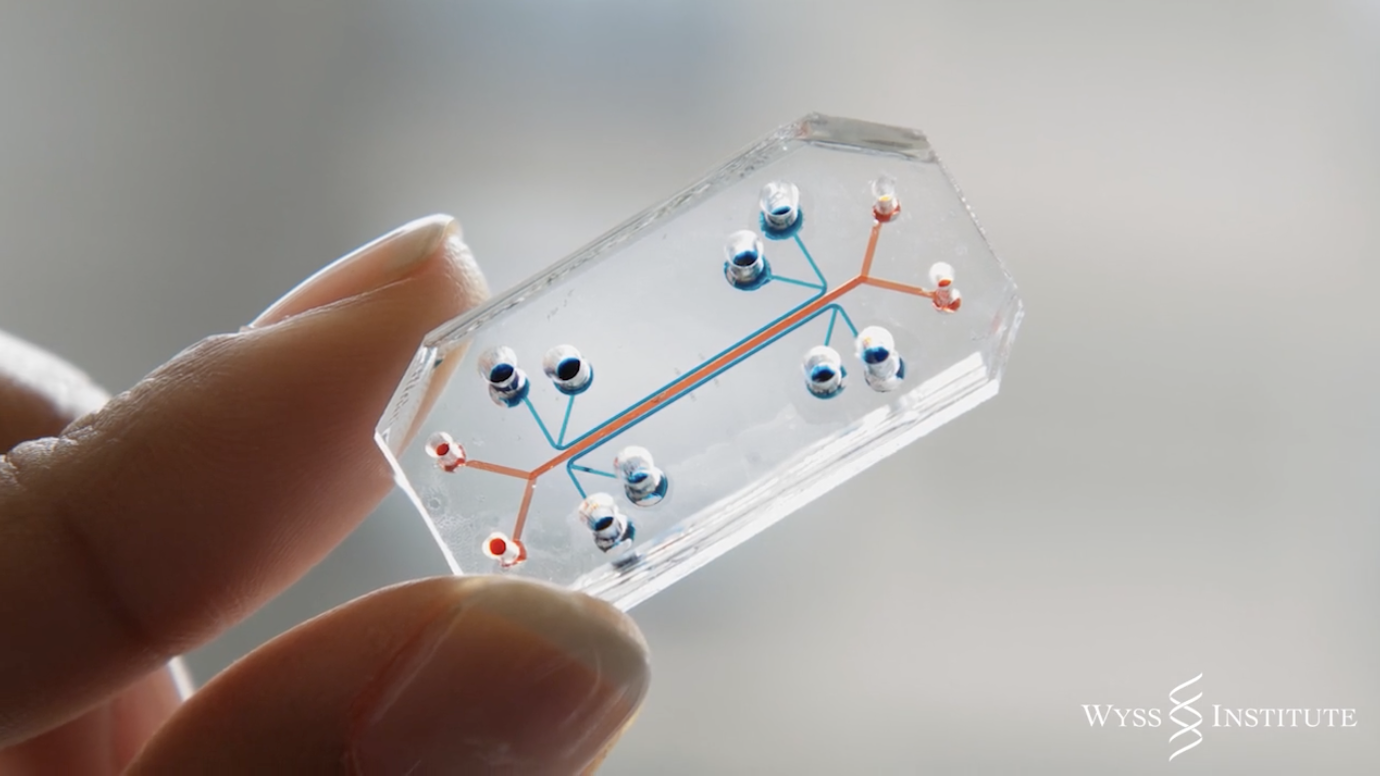

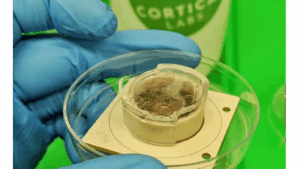

How can a chip breathe, digest, or even mimic a beating heart? Led by Donald Ingber, a team of researchers at Harvard’s Wyss Institute have created a novel, revolutionary way to advance drug development. By mimicking the human body’s natural processes, these “Organs-on-Chips” (OoCs) allow researchers to observe how drugs react with human tissues, offering a significant breakthrough in overcoming the downsides of traditional drug testing.

The Organ on a Chip

Drug development is notoriously slow and expensive, with only 13.8% of tested drugs ultimately gaining FDA approval (1). A major challenge in the drug approval process lies in the reliance on animal models and cell cultures: cells in petri dishes are removed from their natural environment, which can affect their behavior, and treatments that show promise in other animals often fail to translate effectively to humans. This mismatch in initial testing results and biological behavior in humans leads to approved drugs failing, useful compounds never being sold, and ethical concerns (2).

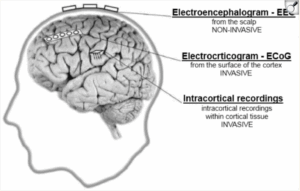

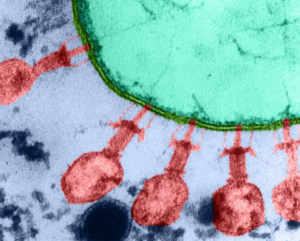

OoCs provide a “home away from home” for cells (3). By mirroring our body’s natural functions, such as tissue structure, biochemical signals, and mechanical forces, OoCs create a more realistic environment for cellular behavior. An example is the lung on a chip, which features two parallel microchannels separated by a thin, porous membrane. The top channel, lined with human lung epithelial cells, is exposed to air to simulate the interface between lungs and the atmosphere. The bottom channel, lined with human endothelial cells, mimics blood vessels delivering nutrients and removing waste. Vacuum channels on either side of the central microchannels apply cyclic mechanical forces to the flexible walls of the device, stimulating the stretching and relaxing motions of breathing (4).

Cross-view of the Lung on a Chip

To test how well the chip imitated lung function, researchers at the Wyss Institute simulated an infection by introducing bacteria into the air channel and then adding white blood cells (5). When bacteria were introduced, the immune cells quickly adhered to the capillary walls beneath the infection site. The scientists then observed the white blood cells moving through the capillary cell layer via the pores in the central membrane and into the airspace, where they attacked and eliminated the bacteria, demonstrating mechanisms identical to those in humans.

The lung chip also showed success in replicating pulmonary edema, a condition in which fluid leaks from the bloodstream to the air sacs. To achieve this feat, researchers introduced interleukin-2, a cytokine-stimulating molecule commonly used in cancer treatment—which is known to cause pulmonary edema as a side effect—at the same dosage typically administered to cancer patients (5). When no movement was simulated, only a small amount of fluid entered the air channels. However, when movements were introduced, the fluid leakage tripled, completely filling the airspace over the same time frame observed in humans. Additionally, blood clots formed in the airspace, mirroring the behavior seen in real cases of pulmonary edema (5).

Building on these advancements, the Wyss team created the “Interrogator” machine, which links up to 10 different organ chips to mimic a full human body (6). The system enables fluid transfer between vascular channels of various organ chips, emulating blood flow and allowing researchers to study interactions between multiple organs. The Interrogator is fully automated, with robotic liquid transfer capabilities that add or sample media as needed. It also includes an integrated microscope for continuous monitoring of tissue integrity, ensuring precise and easy-to-use control (6).

Harvard’s new OoC technology offers a transformative approach to drug development. As this technology progresses, we can look forward to more breakthroughs in drug testing, fewer ethical concerns for animal testing, and more reliable treatments tailored to human biology.

Sources:

- Wyss Institute. (2020, January 27). Human body-on-chip platform enables in vitro prediction of drug behaviors in humans. Retrieved from https://wyss.harvard.edu/news/human-body-on-chip-platform-enables-in-vitro-prediction-of-drug-behaviors-in-humans/

- Wyss Institute. (2014, July 28). Human organs-on-chips. Retrieved from https://wyss.harvard.edu/technology/human-organs-on-chips/

- Hamilton, G. (2013, December 3). Geraldine Hamilton: Body parts on a chip. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CpkXmtJOH84&ab_channel=TED

- U.S. Army. (2020). Army applies lung-on-a-chip technology to COVID-19 research – DEVCOM CBC. Army.mil. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.devcom.army.mil/news/army-applies-lung-on-a-chip-technology-to-covid-19-research/

- Wyss Institute. (n.d.). Lung-on-a-chip. Retrieved from https://wyss.harvard.edu/media-post/lung-on-a-chip/

- Harvard Gazette. (2020, January). Human body-on-chip platform may speed up drug development. Retrieved from https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/01/human-body-on-chip-platform-may-speed-up-drug-development/#:~:text=The%20Interrogator%20instrument%20enabled%20the,instrument%20with%20his%20bioengineering%20team.

Images:

Comments are closed.