Examining what it means to lucid dream and practical methods of induction

Have you ever questioned the very fabric of our existence? Theorized that you aren’t actually real, that you’re dead already, or that, perhaps, everything is just a dream? This curiosity is actually the first step to being able to lucid dream, a phenomenon where you become aware of the fact that you’re dreaming while remaining asleep. Most people have heard about lucid dreaming before, and approximately 50% of the world claims to have had one or more lucid dreams in their lifetime (1). However, there are misconceptions about exactly what it means, how it works, and how to have one yourself.

Lucid dreams are a unique space for curiosity and creativity.

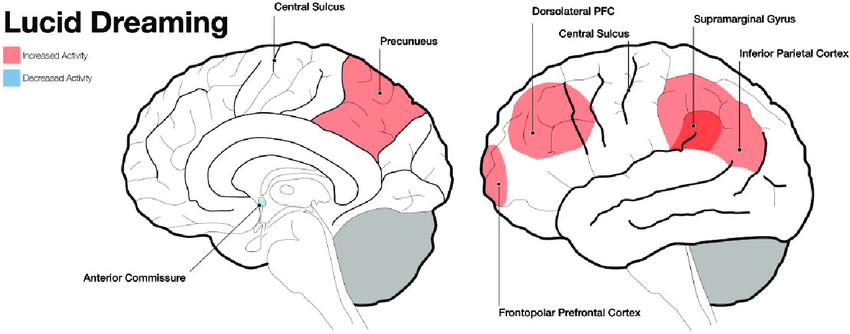

Lucid dreaming doesn’t necessarily grant control over anything in your dream, but being able to manipulate the surrounding dreamscape is often a subsequent effect (2). Everyone experiences lucid dreaming differently, with varying degrees of influence on their environment. These degrees exist on a spectrum, ranging from awareness with little to no control to an ability to willingly materialize your thoughts and alter the course of your dreams. Studies on lucid dreaming found that it occurs during the Rapid Eye Movement (REM) stage of sleep, as is the case with typical dreams. Though unlike regular dreams, the brain is in a state much closer to wakefulness, and the prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain responsible for decision-making and self-awareness—becomes partially active. This activity allows the dreamer to experience a state between subconsciousness and consciousness (2).

Exploring the history and research methods of lucid dreaming clarifies how our understanding of the phenomenon has developed. While proof of its existence dates back centuries, more extensive research on lucid dreaming only began relatively recently. It wasn’t until 1913 that psychiatrist Frederik van Eeden first defined the term “lucid dream,” and it took until 1968 for scientist Celia Green to study it in depth. In the following years, Dr. Stephen LaBerge helped make lucid dream research more mainstream, and new technology led to more detailed and accurate discoveries (2). Scientists conducted research by observing the physical and neurological state of a subject in a lucid dream. Features they measured include brain activity (through neuroimaging), eye movement, heart rate, and respiration (3). Much of what we know about lucid dreaming has been concluded from these studies. Despite all that we’ve found, the science behind dreaming is still somewhat of a mystery. The most significant reason for this is that scientists are unable to clearly communicate with subjects while they’re sleeping, leading to limited research methods. Furthermore, since lucid dreaming occurs inconsistently and in different ways for different individuals, attempts to study it face another layer of difficulty (1).

In order to learn how to lucid dream, it’s important to first understand that certain inconsistencies will always appear between dreamscapes and reality. Our brains are adept at replicating reality through the use of the senses, and because the parts of the brain used for critical thinking are less active during sleep, we experience a sensation called “dream blindness” (3). We become immersed in the dream’s narrative regardless of the absurdity of events. Despite this, it’s possible to train our brains to recognize certain specific details that will always deviate from reality. Three examples are words, times, and light switches: words in dreams aren’t legible, clocks and watches tend to show unreasonable times, and light switches don’t work (4).

Two perspectives of a brain, highlighting the areas of activity while lucid dreaming.

Beyond learning to identify these inconsistencies, other specific induction techniques have been studied more in depth, and you can practice them on your own. One such technique is keeping a dream journal, which helps strengthen your dream recall and reveal patterns that make it easier to recognize when you’re in a dream. Another strategy is the Mnemonic Induction of Lucid Dreams (MILD) technique, where, before you go to sleep, you set an intention to remember your dream when you wake up (4). Consistently practicing “reality checks” multiple times during the day, where you ask yourself if you’re dreaming and how you would know, is another technique that could lead you to ask the same question while in a dream (4). Finally, the “wake back to bed” technique involves literally waking yourself up in the middle of the night with an alarm and then going back to sleep. By doing this, you may be able to fall back into your dream in a more lucid state (4).

Lucid dreaming has the potential to become a way to alleviate everyday stress and help people who suffer from chronic nightmares and various mental health conditions. It allows people to identify and redirect bad dreams and create more relieving situations. This ability is enjoyable to anyone and especially beneficial for people with depression, anxiety, insomnia, or PTSD (1). For people with no preexisting sleep-related health conditions, the only known drawback of lucid dreaming is that induction techniques may interrupt sleep (2). It is overall a safe practice that has various advantages for both your sleeping and waking life.

There is still much to learn about lucid dreaming, and in the coming years, continued development of induction techniques and other technologies will enable scientists to learn more about the conscious and subconscious states of mind, the nature of lucid dreaming, cognitive neuroscience, and sleep research (3).

Sources

- Clinic, C. (2025, July 23). Lucid Dreams: What They Are and Why They Matter. Cleveland Clinic. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/lucid-dreams

- Janzer, C. (2022, April 18). What Is Lucid Dreaming? Sleep.com. https://www.sleep.com/sleep-health/what-is-lucid-dreaming

- Baird, B., Mota-Rolim, S. A., & Dresler, M. (2019). The cognitive neuroscience of lucid dreaming. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 100, 305–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.03.008

- Janzer, C. (2022, April 8). How to Lucid Dream. Sleep.com. https://www.sleep.com/sleep-health/how-to-lucid-dream

Images

Comments are closed.