Unraveling the links between these two organ systems

Rare liver diseases, such as Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC) and Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC), are devastating, incurable afflictions that have long confounded medical professionals and patients (1). Yet what if the key to treating rare liver diseases lies not in the liver itself, but rather in the microbes living in the gut? The “gut-liver axis,” which refers to the relationship between the gut (including the stomach, intestines, and colon) and the liver, holds untapped potential in treating PSC, PBC and other rare liver diseases (1). Given how little is known about these diseases, the gut-liver axis represents a promising target for new treatments.

First uncovered by researchers in 1998, the gut-liver axis is still a relatively new concept in scientific research (2). This bidirectional line of communication between the liver and the gut is facilitated by several key components: the portal vein, bile acids, and the gut microbiome (3). The portal vein, a network of blood vessels carrying blood from digestive organs to the liver, transfers microbial products created in the gut, such as lipopolysaccharides, short-chain fatty acids, and bacterial DNA, to the liver, where they can affect metabolic functions and immune responses (4). Simultaneously, the portal vein transports bile acids and antibodies (which help to regulate immune responses and support gut homeostasis) from the liver back to the gut (1). Bile acids, crucial in liver function, are released into the small intestine after meals to aid in digestion (3). In a healthy system, this flow of substances maintains gut and liver health by regulating immune responses and promoting microbial balance. However, when the system is disrupted—for instance, by antibiotic overuse, a high-fat diet, or chronic inflammation—it can cause conditions like dysbiosis (an imbalance in the gut microbiota) and “leaky gut,” where harmful bacteria, toxins, and microbial products “leak” across the intestinal barrier into the bloodstream and liver, triggering inflammation that may impair liver function (5). Emerging research has shown that disruptions in the gut microbiome can contribute to or worsen liver conditions, as many patients with liver disease often have higher levels of detrimental bacteria and lower levels of beneficial bacteria.

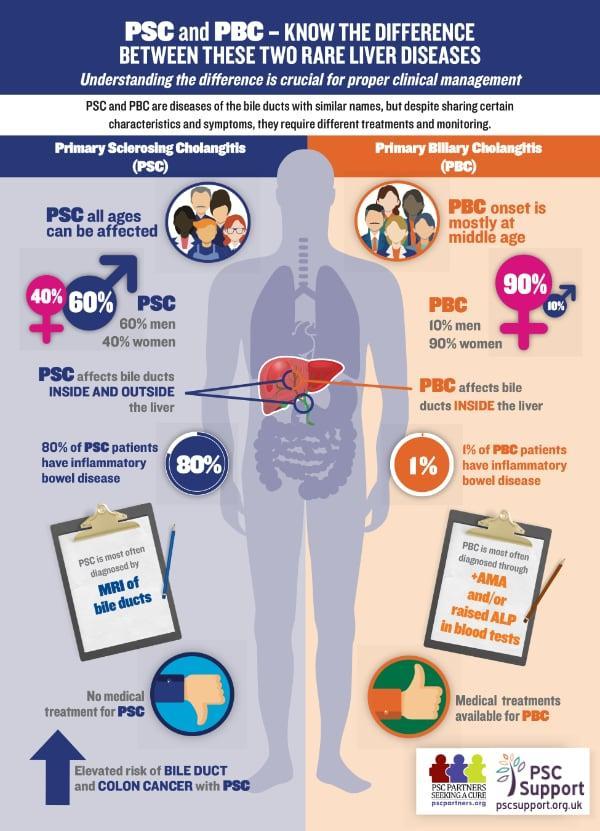

These disruptions can significantly impact rare liver diseases such as PSC and PBC. PSC, which affects up to 1.3 people per 100,000, is a chronic autoimmune liver disease targeting the bile ducts (5). These ducts carry bile, a digestive fluid rich in bile acids, between the liver, gallbladder and small intestine (5). For patients with PSC, inflammation narrows or blocks the bile ducts, reducing bile flow and leading to liver cirrhosis (the scarring of liver tissue) and eventually liver disease (5). Similarly, PBC, which affects between 1.9 and 40.2 people out of every 100,000, is another chronic autoimmune liver disease characterized by reduced bile flow because of the gradual destruction of bile ducts by the immune system (6,3). Similar to PSC, this disease progresses slowly, culminating in cirrhosis and liver disease in some cases (6, 3). The development of these diseases remains poorly understood, but both are linked to disruptions in gut microbiota. The only known treatment for PSC is a liver transplant, and no other effective treatments for this disease exist (5). PBC has a first-line treatment, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), that can slow the disease’s progression; however, this treatment does not work well for many patients, highlighting the need for a new therapeutic agent—a role that gut microbiota-based treatments could fill (3).

PSC and PBC infographic (1).

Because researchers have found that those with PSC or PBC often have altered gut microbiota, recent treatment efforts have focused on reestablishing a healthy gut microbiome. This includes the use of probiotics, which are live microorganisms that promote gut balance and repair dysfunction, and bacterial metabolites (post-biotics), which are byproducts of microbial organisms that may promote liver health by reducing inflammation (1). Furthermore, some medical researchers have used a process called fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), where a fecal suspension sourced from a healthy donor is transferred to the digestive system of a patient, to promote gut balance (5). While these emerging treatments show promise, current research is not yet sufficient to prove that they could be used as treatment in a clinical setting.

Researching potential treatments for rare liver diseases is a challenging process: most studies are too small, and the gut microbiome is so diverse that it is difficult to pinpoint the exact balance of microbiota that will be most beneficial. There are over 100 trillion microbes in the gut, more than ten times the number of cells in the entire human body, so decoding the links between gut bacteria and disease remains a complex problem (7). While more time and research is needed to better understand the intricate interactions between the liver and the gut, it seems clear that the future of rare liver disease treatment lies in unraveling the cryptic connections between the liver and the body’s microbial ecosystem.

Works Cited

- Albillos, Agustín, et al. “The Gut-Liver Axis in Liver Disease: Pathophysiological Basis for Therapy.” Journal of Hepatology, vol. 72, no. 3, Mar. 2020, pp. 558–77, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.10.003.

- Bragazzi, Maria Consiglia, et al. “Role of the Gut–Liver Axis in the Pathobiology of Cholangiopathies: Basic and Clinical Evidence.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 24, no. 7, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, Apr. 2023, pp. 6660–60, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24076660. Accessed 21 Jan. 2025.

- Zhang, Li, et al. “Targeting Gut Microbiota for the Treatment of Primary Biliary Cholangitis: From Bench to Bedside.” Journal of Clinical and Translational Hepatology, vol. 000, no. 000, Mar. 2023, https://doi.org/10.14218/jcth.2022.00408. Accessed 16 Oct. 2023.

- Kotlyarov, Stanislav. “Importance of the Gut Microbiota in the Gut-Liver Axis in Normal and Liver Disease.” World Journal of Hepatology, vol. 16, no. 6, June 2024, pp. 878–82, https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v16.i6.878. Accessed 29 Sept. 2024.

- Burcin Özdirik, et al. The Role of Microbiota in Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis and Related Biliary Malignancies. no. 13, June 2021, pp. 6975–75, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22136975. Accessed 1 June 2023.

- Kumagi, Teru, and EJenny Heathcote. “Primary Biliary Cirrhosis.” Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, vol. 3, no. 1, Jan. 2008, https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-3-1. Accessed 22 Feb. 2020.

- Ferranti, Erin P., et al. “20 Things You Didn’t Know about the Human Gut Microbiome.” The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, vol. 29, no. 6, 2014, pp. 479–81, https://doi.org/10.1097/jcn.0000000000000166.

Image Link:

Comments are closed.