A technological advancement of gene editing discovered at MIT and Harvard

Genome editing is a groundbreaking technology that allows scientists to make rapid, precise, and accessible changes to DNA. This technology has the potential to treat genetic disorders, modify crops, and tackle global challenges (1). Recently, a research team at MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research discovered Fanzor, the first programmable RNA-guided system in an eukaryotic organism, which unlocks novel potential in genome editing (2).

DNA is made up of four molecule bases (adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine) which get grouped into sequences called genes. Genes program our body’s functions and vary in length, ranging from a hundred bases to a million (1). Gene editing is a technology that allows scientists to change an organism’s DNA sequences through the removal, alteration, and addition of genetic material (3). Depending on the task, DNA segments can be removed, singular bases can change, or whole sequences can be added (1).

(https://www.ucl.ac.uk/ioo/research/research-labs-and-groups/carr-lab/bestrophinopathies-resource-pages/research/research-3) How genome editing works to modify genetic diseases

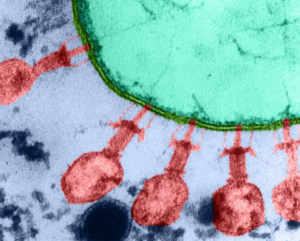

Genome editing was discovered through CRISPR-Cas9—clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats with protein Cas9—a system found from bacterial immune defenses. Bacteria capture viral DNA to create CRISPR arrays which remember the viruses, so when a virus next forms, RNA from these arrays are released to guide enzymes, like Cas9, to cut the DNA. Researchers modified this defense tendency by creating RNA to guide enzymes in cutting specific DNA sequences. While there is much reward from genome editing technology, it is still subject to many unfixed problems (3).

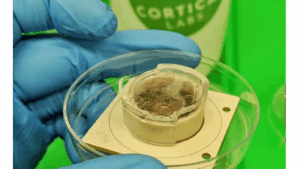

In 2023, a discovery by a group of MIT and Harvard scientists, led by Feng Zhang, uncovered a breakthrough in gene editing: the first programmable RNA-guided system in a eukaryotic organism—an organism which contains a nucleus—named Fanzor. Zhang initially wanted to develop a genetic medicine with technology beyond CRISPR, discovering a new RNA-programmable class in eukaryotes, called OMEGAs. The similarities in eukaryotic OMEGA systems and eukaryotic Fanzor proteins suggest Fanzor enzymes also use a RNA-guided system to target and cut DNA. Unlike CRISPR, Fanzor has performed in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms, specifically having enzymes encoded in the eukaryotic genome within transposable elements. Studies show that Fanzor proteins use ωRNAs, non-coding RNAs, to target genome sites, unlike most gene editing technology. Fanzor proteins improve CRISPR-Cas9 by enhancing RNA’s precision, enabling edits of genes from eukaryotic cells, and making delivery to cells and tissues easier than prior technologies. Even though Fanzor is a new tool in genome editing, through refinements and more research, its capabilities are unprecedented (2).

Looking ahead, Fanzor’s improved functions address many gene editing issues with more accurate and accessible edits, while remaining effective in eukaryotes. Its precise targeting and reprogramming of genomes makes it the right choice for gene therapy, treating genetic diseases using its specific changes to DNA. In addition, unlike CRISPR and OMEGA systems, Fanzor avoids collateral activity, where enzymes fall off track from their target DNA and degrade nearby RNA and DNA, reducing unwanted outcomes. This breakthrough allows gene therapy, especially with genetic diseases, to ensure safer and successful results than before (2).

While genome editing has many advantages, it raises ethical, social, and safety concerns. People have worries about the pressure on scientists, the creation of mutations affecting future generations, and drawing the line between treatment and enhancement. Additionally, social and economic inequality in society offer disadvantages to people who can’t afford treatment. (4).

Genome editing, especially with breakthrough discoveries like Fanzor, has shifted the potential of healthcare, agriculture, and genetics. This technology could revolutionize our daily lives. However, with these promising rewards, there are equally as many safety and ethical concerns we must acknowledge and address before implementation. With continued research and development, genome editing, particularly Fanzor, has the potential to take over the world.

Sources:

- Bowen-Metcalf, Gavin. (2023, February 14). What is gene editing and how could it shape our future. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/what-is-gene-editing-and-how-could-it-shape-our-future-199025#:~:text=Gene%20editing%20has%20its%20advantages,mankind%20while%20minimising%20the%20risks.

- Eisenstadt, Leah. (2023, June 28). Researchers uncover a new CRISPR-like system in animals that can edit the human genome. MIT News. Retrieved from https://news.mit.edu/2023/fanzor-system-in-animals-can-edit-human-genome-0628

- (2022, March 22). What are genome editing and CRISPR-Cas9. Medline Plus. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/understanding/genomicresearch/genomeediting/

- Todd Bergman, Mary. (2019, January 9). Harvard researchers, others share their views on key issues in the field. The Harvard Gazette. Retrieved from https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2019/01/perspectives-on-gene-editing/

Comments are closed.