How did Boston’s hospital find the cure for the Polio virus?

The cure for polio, one of the most rampant infectious diseases in United States history, originated in Boston, Massachusetts at Boston Children’s Hospital. Polio breakouts began in 1916, with annual summer surges. The summer months allowed the disease to spread more rapidly with increased close contact among children. Polio primarily affected children and caused muscle weakness and temporary or permanent paralysis. Respiratory paralysis, when the body cannot breathe on its own, made polio especially deadly (1, 2). From the 1940s to the early 1950s, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that polio paralyzed over 30,000 people annually (2). Dr. Mark Rockoff of Boston Children’s Hospital described polio as “probably the most terrifying infectious disease that existed” (1).

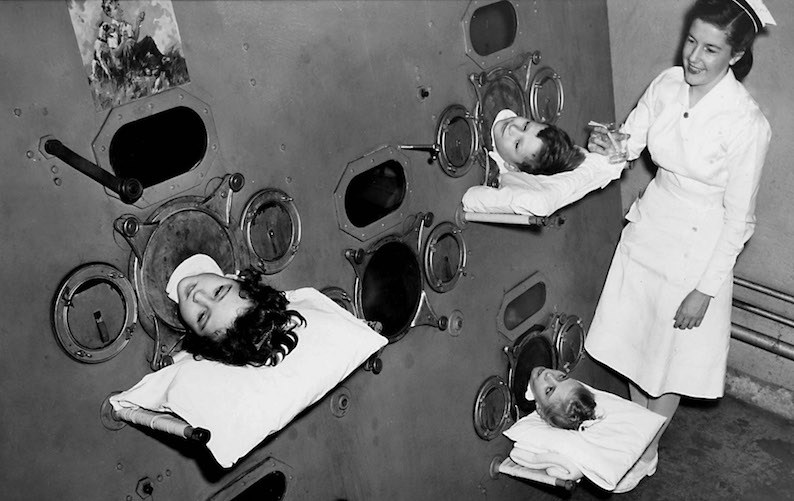

While some polio patients exhibited no symptoms, others became partially or completely paralyzed for the rest of their lives. Some patients who suffered from paralysis could not breathe on their own. Due to the lack of respirators, machines designed to assist breathing, many lost their lives. (2) In 1928, engineer Phil Drinker invented the iron lung, a pressurized chamber powered by a vacuum-cleaner motor. The massive machine allowed polio patients to breathe while their bodies regained function of their chest muscles. The iron lung saved lives, but it was not a cure. Some patients did not survive polio even with the iron lung’s assistance (2, 5).

Polio patients in an iron lung machine.

There was a major breakthrough in vaccine development in 1949 when researchers from Boston Children’s Hospital––John Enders, Thomas Weller, and Frederick Robbins––developed a method to culture poliovirus in human skin and muscle cells. This innovation earned them the Nobel Prize in Medicine and demonstrated a pivotal step in polio research (3). Culturing the virus allowed scientists to study it in a controlled environment and facilitated the development of the vaccine (2). In 1953 Jonas Salk used these cultures to develop an injectable inactive polio vaccine (1). He grew poliovirus on monkey kidney cells and inactivated them with formalin, a common disinfectant. In April of 1955, after the vaccine was tested in a trial involving 1.6 million children, it was first administered in the United States. (7) Albert Sabin later created an oral vaccine using weakened live poliovirus (2). These vaccines drastically reduced polio cases globally (3). By 1980, the disease was officially eradicated in the United States, and in 1994 it was gone in North America (6).

A news clipping from May 1, 1962.

The physicians and scientists at Boston Children’s Hospital were vital in treating and preventing polio (2). Polio’s impact extended beyond medicine. Many survivors with disabilities played key roles in the Disability Rights Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. The movement promoted visibility for those with disabilities and led to legal protections such as the Americans with Disabilities Act, a civil rights law that prohibits discrimination against disabilities (3). The work done at Boston Children’s Hospital demonstrates the importance of using different angles of scientific research, such as engineering, in fighting public health crises (1).

Bibliography

- Herwick, E. (2016, October 14). How Boston Children’s Hospital took on polio and won. WGBH. Retrieved from https://www.wgbh.org/news/national/2016-10-14/how-boston-childrens-hospital-took-on-polio-and-won

- McAlpine, K. (2017, April 20). Poliovirus. Boston Children’s Hospital. Retrieved from https://answers.childrenshospital.org/poliovirus

- (2020). Polio vaccine. Boston Children’s Hospital Archives. Retrieved from https://bcharchives.omeka.net/exhibits/show/polio/vaccine#:~:text=Boston%20Children’s%20researchers%20John%20Enders,of%20a%20vaccine%20to%20begin

- (2022, October 22). Poliomyelitis. World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/poliomyelitis

- (2020, April 3). From iron lungs to modern ventilators: A look at respiratory care. Barlow Respiratory Hospital. Retrieved from https://www.barlowhospital.org/news-room/2020/april/from-iron-lungs-to-modern-ventilators-a-look-at-/

- (2020). History of polio: Disease outbreaks and vaccine timeline. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/history-disease-outbreaks-vaccine-timeline/polio

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3782271/

Comments are closed.