What are flexor tendons, how are they injured, and how are they repaired?

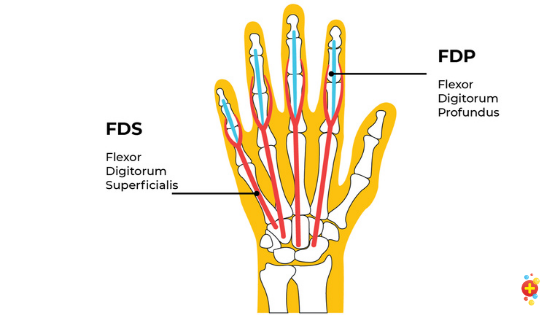

Flexor tendons are structures in the fingers that allow for contractions and enable gripping motions. These tendons connect the muscles in the forearm to the bones in the hand, enabling coordinated and controlled movements. However, they are also vulnerable to injury, particularly from trauma or deep lacerations, which may result in loss of function if not given medical attention. There are three primary flexor tendons: flexor digitorum profundus (FDP), flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS), and flexor pollicis longus (FPL). The FDP flexes the distal phalanges, thin bones in the fingers, while the FDS is responsible for flexing the middle phalanges (1). The FPL is the more notable one that exclusively controls the thumb movement. These tendons collectively facilitate the flexions of fingers.

The main flexor tendons.

The two primary tendons in the fingers are the FDP and FDS. The FDP is responsible for bending the tips of the fingers, while the FDS controls the middle segments (middle phalanges). Each of these tendons runs along the fingers and passes through a series of tunnels, known as fibrous sheaths, which help secure the tendons close to the bone and guide their movement during flexion (1). In the thumb, the FPL serves a similar purpose as the FDP, controlling the flexion of the thumb. A synovial sheath, a lubricated, fluid-filled covering, surrounds the tendons. Unlike the fibrous sheath that secures the tendons, it allows for smooth, low-friction movement. Each tendon is composed of parallel collagen fibers that provide both strength and elasticity. However, due to their complex structure and delicate interaction with nearby nerves and blood vessels, even minor damage to the flexor tendons can result in significant functional loss, making their anatomy critical in both hand movement and injury repair (1).

Flexor tendon injuries often result from cuts or trauma and usually require surgery for full recovery. These injuries are typically divided into five different zones based on their location in the hand. Zone 1 is allocated to injuries near the tips of the fingers, affecting the FDP, which controls flexion of the distal phalanges. Zone 2, covers the regions of the middle of the palm to the middle phalanges. It has earned the moniker “no man’s land” because it has notoriously dense fibrous sheaths that limit the space for surgical intervention. Zone 3 is in the palm area, where tendon injuries tend to be easier to repair because there is more tissue and less complexity compared to Zone 2. Zone 4 involves the carpal tunnel region, where the tendons, median nerve, and blood vessels are tightly packed, making injuries here particularly complex. Damage to this area can involve both tendons and nerves. Zone 5 covers the forearm near the wrist. Injuries in this area often occur due to more severe trauma, like industrial or vehicular accidents, and can damage multiple tendons, nerves, and blood vessels (2).

Symptoms of a flexor tendon injury include the inability to bend the fingers, swelling, tenderness, pain in flexing the palm, and visible open wounds if the injury involves a laceration (1). A key sign is the “Jersey Finger” deformity, often seen in sports injuries, where the fingertip remains straight despite the attempt to flex it (3). This is due to a flexor tendon avulsion, where the tendon is forcibly torn apart from the bone (3). This type of injury frequently affects the ring finger due to its vulnerable position and can be especially challenging to treat.

The phenomenon known as “Jersey Finger,” where the tendon is torn from the bone.

Given that flexor tendons play such an essential role in hand movement, these injuries can severely limit a person’s ability to perform everyday tasks. Without timely medical intervention, untreated flexor tendon injuries can lead to permanent stiffness, scarring, and functional loss. Early diagnosis and surgical repair and rehabilitation are vital. Applying IV antibiotics and debridement is the starting procedure with the patient being educated about the importance of follow-up care and compliance to ensure optimal recovery (2).

Surgery is the standard treatment for complete flexor tendon lacerations, although not all injuries may necessitate such an immediate intervention. Primary repair is preferred within the first 24 hours for clean injuries with fewer complications. However, for more contaminated or infected wounds, delayed primary repair (24 hours to 2 weeks) is often necessary (2). In the scenario where the injury is severe or already infected (or presented late), secondary repair is considered, though it carries a much higher risk of complications (infection and prolonged swelling). In cases where tendon repair gets delayed beyond five weeks, surgical options such as tendon grafting or tendon transfer become imperative due to a significant loss of tendon or muscle contraction (2). This process usually involves harvesting a tendon from another part of the body and using it to replace the damaged portion.

The use of advanced suturing (stitching) techniques, such as multi-strand core sutures, helps increase the strength of the repair and allows for early mobilization, reducing the risk of adhesions. However, care must be taken to balance strength to flex the finger with the need for smooth tendon gliding within the sheath, particularly in the challenging Zone 2 injuries (2).

Flexor tendon injuries are complex and require careful management. Initial treatment is critical for preventing infection and stabilizing the wound. Surgical options vary depending on the timing and severity of the injury, with primary repair being the preferred method for early intervention. When the injury is severe or presents late, tendon grafting or tendon transfer may be necessary. With modern techniques and diligent rehabilitation, many patients can regain function in their hand, though complications such as adhesions, re-rupture, and stiffness remain concerns.

Bibliography:

- Caruso, J. C., & Patiño, J. M. (2020). Flexor Tendon Lacerations. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved September 30th, 2024, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493223/

- Flexor Tendon Injuries – OrthoInfo – AAOS. (n.d.). Www.orthoinfo.org. Retrieved September 28, 2024, from https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases–conditions/flexor-tendon-injuries/

- Abrego, M. O., & Shamrock, A. G. (2020). Jersey Finger. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved September 28, 2024, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545291/

Images:

- Finger Tips – tendons and ligaments. (2020). In Don’t Forget the Bubbles. Retrieved September 28, 2024, from

https://dontforgetthebubbles.com/finger-tips-tendons-and-ligaments/ - Abrego, M. O., & Shamrock, A. G. (2023, August 7). [Figure, Jersey finger. Image courtesy O.Chaigasame]. Www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545291/figure/article-36511.image.f1/

Comments are closed.